Further to my article on Newgate, here’s an excerpt from Encouraging Prudence.

Chapter 13

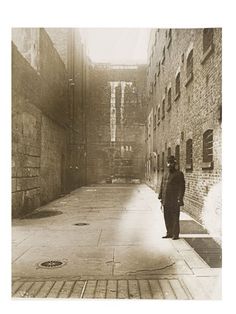

The gray walls of Newgate shadowed the street, and the stench of human despair reached out, so strong that Prue imagined it had a bodily presence that would drag her through the felons’ door and into the prison.

She froze before the heavy door, and one of the guards shoved her forward, roughly but without malice. “Not going to get better if’n you stand here,” he told her.

Inside, the system moved into ponderous action. She, and the charges against her, were catalogued, and she was passed into the hands of the prison staff. She felt a wave of horror as the guards left her alone with the keepers, as if her last connection with the outside world was walking away from her.

No. David would not abandon her. She had only to endure until he could make arrangements.

“P. Worth. Thief and murderer,’ the keeper who had spoken to the guards reported, as he ushered her into a dirty cramped little room where two keepers waited, one behind an untidy desk, and the other hunched over a meagre fire.

“Accused, awaiting trial, and innocent,” Prue said, amazed that her voice sounded so calm when she had to force it through a throat stiff with panic.

The keepers both snorted their amusement. “How much?” the one behind the desk asked.

Prue had no idea what he was talking about. “How much what?”

“Money. How much can you pay for a bed? For food?”

The runners had taken all of her money along with the money and jewels planted in her belongings. She had nothing. David would come. She had to believe that.

“A friend of mine is coming. He will bring whatever money I need.”

“Your friend,” he managed to invest the word with salacious meaning, “isn’t here now. We need money up front, not a thief-whore’s promises.”

“I have no money on me, but Mr Wakefield will take care of it when he comes.” She would not panic. She could endure this.

The man behind the desk shook his head. “Have to be paid, sweetheart. Cash or kind.”

The other man, the one in front of the fire, spoke for the first time, “We could be kind if she was kind, what do you say, Merton?”

They leered at her, and she glared back. “Mr Wakefield will avenge any insult to me,” she told them.

Something got through to them. Her assumed confidence, perhaps, or her upper class accent. They exchanged uncertain glances, then frowned at her. The bully behind the desk came to a decision. “Right, then. We’ll ‘ave that dress. Worth a bob or two that is.”

“And the shoes,” chimed in his accomplice. “Three shillings the shoes, two shillings the dress. Get you a bed in the main ward for a week, that will. Can’t do fairer than that.”

Prue backed against the wall. They weren’t seriously intending to take her dress and shoes, were they?

They were. “Come along, off with them. I could ‘elp you, if you like.” The accomplice approached her, his leer stirring old ghosts so that she had once again to swallow against a suddenly closing throat.

“Hold them safely,” she instructed coldly. “Mr Wakefield will redeem them when he comes.”

The stone of the floor struck cold up through her stockinged feet, and cold radiated off the grimy stone of the passage walls as the two keepers escorted her through the prison in her shift. She was battered on every side by the constant din — shouting, screaming, screeching, crying, and various unidentified bangs and clatters. And the rank smell got worse the closer they came to the place where she was to be confined.

One keeper unlocked the door while the other attempted to put his arm around Prue. She slid sideways to evade him.

In response, he gave her a rough shove through the doorway, so that she stumbled and almost fell. The door clanged shut behind her, audible even through the tumult that her entry had barely dented.

She was in a open space — a courtyard around 40 feet long and 10 feet wide made smaller by the number of women and almost twice that number of small children occupying it. Three tiers of rooms had barred windows onto the courtyard. Through the door of the nearest one at ground level, she could see rows of pallets on the floor.

Slowly, her eyes began to make sense of the constant churning movement: children running in and out of groups of women who were arguing, gossiping, playing cards and throwing dice, cooking over small fires, nursing babies, disciplining toddlers, drinking, eating, and shouting. In one corner, an argument descended into a hair-pulling fight, and further down the yard, a group of women who had been singing suddenly broke into a high-kicking dance, arm in arm in a long line.

The noise was indescribable, but not as intensely offensive as the smell: rotting food, human waste, unwashed bodies, all blended into a stench that made the inside of her nostrils feel grimy.

She would burn her stockings and her shift when she was free of this place.